The media is a crazy world. There has been a growing confusion as to what the media is supposed to be. Today, anybody can disseminate news. Anybody can be a journalist. Why should the media exist, anyway? Why must the media sector be studied or listened to anyway? This story gathers journalists around the media sector to talk to us why the media still matters today.

The media is a public sphere. Funded by advertisers and business to survive, it is an area for discussion of different events that shape the way we live. The danger of this openness is its vulnerability to prejudice, misunderstandings, economic agendas, censorship, and control. An Xiao Mina expounds on this: “Without proper care, public spaces like the Roman Forum — designed first and foremost as a place for commercial and state business — can readily become places of exclusion, rumor, disease, politicking, exploitation and open violence as they steadily approach entropy.” Because of this, it is a must to emphasize that journalism is not simply an area for discussion. The media is the mediator. The aim of its open discussions is to first, ensure that everyone has access to information. The media has made efforts to adjust to the public’s time to deliver news. According to Sarah Marshall, late evening is peak time for active audiences. “An opportunity to engage audiences. When writing or creating products, editors, reporters, and UX designers should therefore consider the reader sitting up in bed looking at her phone.” With the rise of social media and audiences who comprehend information better through websites, mobile applications, and short news clips posted online, Rappler, Philippine Daily Inquirer, Manila Bulletin, Philippine Star, and many other news sites have established their online presence respectively. The goal is to find different ways to ensure that everyone gets information. This is written in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” Access to information is important because a free press is parallel to a free society. Access to information implies one’s right to freedom and self-government. You have the free will to act upon the information you have received. Most importantly, as a member of society, you have a responsibility to participate in whatever way you can, especially if the news constitutes a social issue. In this light, access to information is communal, a way to build society for the better.

Frankly, there’s a media hierarchy

How pressing would it be if not everyone had access to news? Sarah Stonbely enlightens us on this: “News inequality matters in the same way that unequal access to education matters: Without trustworthy, reliable local and national journalism, the democratic political system breaks down.” To emphasize, news inequality widens the gap among sectors of society. The call for participation will lower in volume, and problems will only be stacked on each other. In relation to the widening gap among people in society, under news inequality, those who have access to news can only participate. It is them, consequently, who will have the power and authority, strengthening the concept of privilege. “There are no voiceless people. There are only people whose voices the industry has chosen not to amplify.” Imaeyen Ibanga said. An example would be news on land ownership and use. A real-estate developer plans to build another condominium in Cavite. Because of their money and power, they can easily pass the news to people to attract buyers of their units. However, we don’t hear from the less privileged, or the farmers to cultivate the land to be used by the real-estate developer as their only source of income. Due to their lack of access to news, there is no awareness that the land they labor on will be taken away from them. There is no reason, subsequently, to speak up for their right to work, until construction workers arrive at the land and start throwing cement and hollow blocks on their crops. The aforementioned is a domino effect, encompassing issues on poverty, labor, and agriculture. We can credit news inequality for the lack of representation of less privileged sectors in society. Journalism is a bullet that mediate the gap among people in the public sphere.

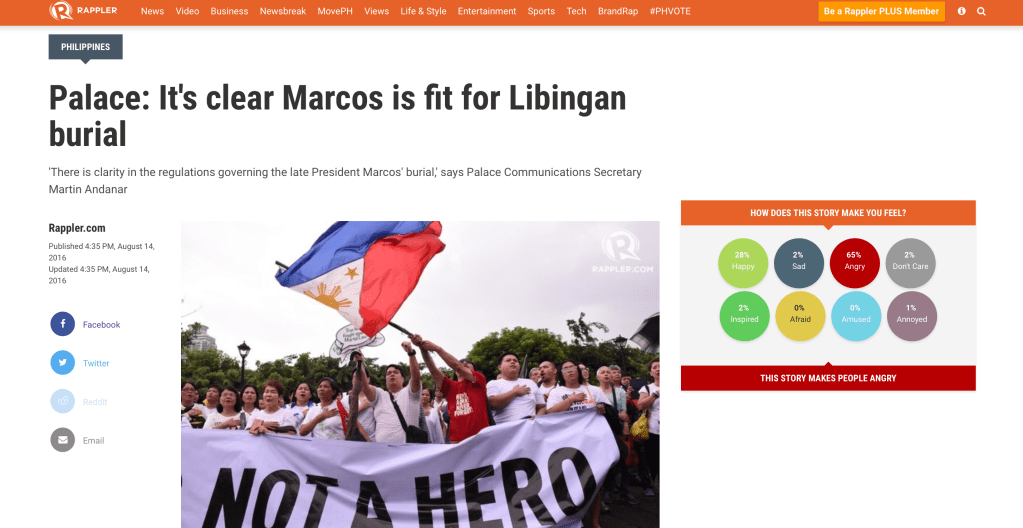

As journalism becomes the mediator in the public sphere, the way news is presented is very crucial to inculcate in readers’ minds that their participation in as a member of society is very crucial. The media is the agenda-setter. The media dictates what is important to talk about, and what details the people must know for them to govern themselves rightly. An example of this would be an article Rappler posted on August 14, 2016, entitled, “Palace: It’s clear Marcos is fit for Libingan burial”. It simply talks about President Rodrigo Duterte’s decision to lay former strongman Ferdinand Marcos’ body at the Libingan ng mga Bayani. Come to think of it, information about one’s place of burial must not really be a big deal. It is simply laying a body to rest. However, the news article frames the decision of the administration that the late dictator deserves to be treated like a hero:

“Last August 7, Duterte said that “as a former soldier and former president of the Philippines,” Marcos is qualified to be buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani.

On August 12, the President reiterated his view, saying, “Even if he is not a hero, he was a soldier. Even if he didn’t receive the medals, correct, but that is the record of another country. Why would I, in making a decision, refer to the records of another country? We have long ceased to be a vassal state of the United States. Tapos na ‘yan (That’s over). It’s history.”

The media and its inevitable power

Alice Antheaume affirms this, “It’s not just a matter of semantics: The ways journalists decide what they cover — and how they think about the shape of that coverage — has an impact on the world.” The media’s manner of framing the issue could be credited for the nationwide protests and revolts that followed Malacañang’s decision.On November 25, 2016, The National Day of Rage and Unity pushed through at the Quirino Grandstand in Manila. Mass actions simultaneously happened in Central Luzon, Southern Tagalog, Bicol, Cebu, Iloilo, Leyte, Roxas, Bacolod, Aklan, Cagayan de Oro, Iligan, Davao, Zamboanga, Sarangani, and Surigao. A lot of the participants in the rallies were younger generations, people who weren’t born between 1972 and 1986, with no firsthand experiences of the horrors of the Marcos regime. The youth felt that sense of purpose to participate with the Palace’s decision, voicing out their dissent. Framing gives the proper context of a news story. It then enables mass participation, manifesting representation, signifying that journalism is a public sphere, and not a privatized sector only.

But there are other powerful forces too

The media, however, instead of being a public sphere, has become a marketplace. It has become a venue for transactions, with envelope journalism becoming more prominent. Advertisements play a big role in funding newspapers, hence the many spaces advertisers take instead of reserving it for news. Another, newspapers have been owned by powerful conglomerates that control other businesses and sectors. Philippine Star is owned by MediaQuest Holdings, a conglomerate owning PLDT, TV5, Nation Broadcasting Corporation, and the like. ABS-CBN News, a reputable news source to the masses, is under ABS-CBN Holdings Corporation, which also controls different media channels/companies: radio (DZMM 630) sports (S+A), music (Myx, Star Records), film (Cinema One, Star Cinema). Joshua Darr reaffirms this “massive infusion of political cash into the media will benefit tech companies and cable news networks more than in previous cycles.” Instead of being the mediator that makes people complacent and aware of what’s happening around them, there is an unequal access to news, favoring those who are privileged to buy newspapers and be educated with media literacy. Instead of setting the agenda of what to talk about and how we must view facts, misinformation is a virus that spreads fast. Instead of being the agenda setter, the existence of other sources of news (due to social media) has caused confusion among the public on what to believe in and what is true. The lack of context and fact checking are two factors that result in this. Despite all this, what remains consistent is the zeal for service of journalists. What is emergent is journalists’ desire to make a public sphere, an open space for everyone to be informed and be represented. Heather Bryant notably said, “The question of how we save journalism (meaning newsrooms) will begin to shift to how do we save journalism (meaning the process).” We must go back to the three definitions of the role of media. It is through these characteristics that the media brings good journalism to the people.

The call to move ahead

Noticeably, the local and international media landscape is not just in charge of disseminating information to the people. It is in charge of fact checking. With the emergence of citizen journalism, it is a must for media practitioners to move a number of steps ahead.

There are a number of media organizations that stand by the mission to save journalism. One of them is the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ). It is one of the most reputable media organizations, known for exposing Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s “Hello Garci” scam in 2004 and the Pork Barrel scam in 2013. First, they do not have printed copies of their stories, as they are in charge of funding investigative projects for both print and broadcast media. Another, they remain steadfast in fact checking despite the emergence of misinformation, as well as trolls who threaten how steadfast they can be. Not to mention, their address is not mentioned in their online sites for security purposes. Additionally, their office unlike other media organizations: a little office, with no big tarpaulins that have their name in bold letters. PCIJ remains predatory with caution, an example of staying true to bringing good journalism while keeping its eyes on the media’s signs of the times.

Today’s challenge in the media landscape does not only require good journalism. On the other hand, misuse of the algorithms of media can result in misinformation. There must be a balance between the two.

Far in the future, the media landscape will change. However, we need a public sphere. We need a mediator. We need representation. With all this, no matter what happens, the role of media will remain universal. They have to make their presence felt to stand the test of time.